Separating low proficiency from low ability is complicated, although necessary for the determination of DLD in bilingual children. Of general concern are the reported higher rates of learning difficulties among children from minority language backgrounds beyond third grade ( Artiles, Rueda, Salazar, & Higareda, 2005) and problems with underidentification of impairment during the early school years ( Bohman, Bedore, Peña, Mendez-Perez, & Gillam, 2010 Collins, O'Connor, Suárez-Orozco, Nieto-Castanon, & Toppelberg, 2014). Age at time of assessment may also influence performance on language tasks, as younger children are generally perceived to be more vulnerable to the effects of L1 suppression in an immersion context.

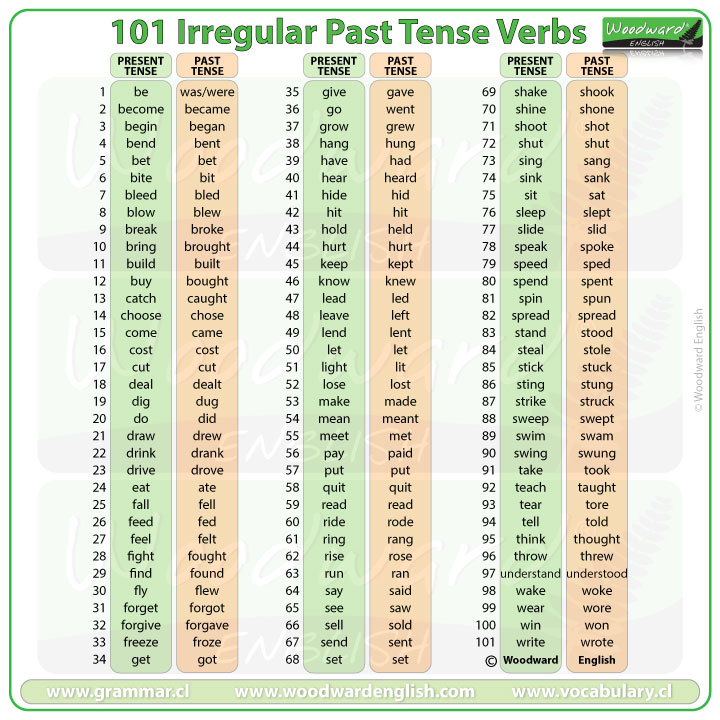

Variation in bilingual versus monolingual learning context may also alter the pattern of deficit in the respective languages ( Morgan et al., 2013). Changes to each language, known as bilingual effects, can result in error patterns that simulate impairment or delay in both languages ( Castilla-Earls, Restrepo, Perez-Leroux, & Gray, 2015 Kohnert, 2010). The diagnosis of DLD in bilingual children is complex. Grammatical deficits are most common, although the problems often extend to other cognitive functions, such as memory, visual rotation, perception, attention, speed of processing, and executive functions ( Schwartz, 2017). Importantly, pieces of evidence of deficits in both languages are essential for the diagnosis of DLD in bilingual children. The estimated prevalence of DLD is 7% in monolingual English speakers ( Tomblin et al., 1997) a similar prevalence is assumed for bilingual children. Consequently, DLD is employed throughout our article even for previous research that used other terms. Although SLI has been the preferred term in research practices ( Leonard, 2014 Schwartz, 2017), use of the term DLD coincides with international efforts to reduce the confusion involving separate terms for research and clinical practice. All describe a heterogeneous grouping of children who, for no apparent clinical reason (e.g., hearing loss, intellectual disability, neurological impairment, behavioral disorder, or structural deficit), exhibit unusual difficulty in acquiring language ( Leonard, 2014). Fluctuations in the amount and quality of English input received at different stages of learning may result in qualitative differences that include features influenced by the first language (L1) or usage patterns characteristic of other children and adults in the community who may be in the intermediate stages of learning English ( Hoff et al., 2012 Morgan, Restrepo, & Auza, 2013 Paradis, 2010).ĭevelopmental language disorder (DLD) is a term recommended to replace previous terminology (e.g., specific language impairment primary language impairment or simply, language impairment ). Active use of more than one language may result in a profile for each language distinct from that of monolinguals. Compared with other languages spoken in the United States, Spanish is ranked as the language that is used most often (57 million speakers) and most likely to be maintained ( U.S. This study shows the need for data on the linguistic status of normally developing children above the age of seven, if we are to make any inferences about the performance of children whose development is deviate.Developmental language data for children who learn English as a second language (L2) while maintaining Spanish are scarce. Analysis of error patterns indicated that learning disabled children used a different pattern of responses and a different set of rules to mark past tense. Children in regular classes showed significantly higher correct responses across 10 categories of past tense items. Neither group has mastered the /-ed/ nor seven categories of irregular past tense markers. Results indicated that both normal and learning-disabled children had achieved control of future, present, and /-d/ and /-t/ past tense markers. Sixty learning-disabled children with a mean age of 7-11 and 60 children in regular classes with a mean age of 7-10 were given a tense marker test to elicit future, present, and past tense markers for 50 verbs organized into 10 categories based on the operation required to form the past tense.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)